1940’s Fashion – A Tiny Study

Clothing

Women

When war broke out, fashion was sure to come under fire as the country came under the shadow of austerity and sacrifice. There was much disagreement between those that thought it a duty for women to look as good as possible for morale and those that thought frugality was necessary. Common sense and compromise eventually prevailed ‘If you want to be in the fashion – be simple.’

An illustration from 1940 pointed out that “nobody these days is bothering about having a great number of clothes – the ideal thing is to possess a few good outfits that can be juggled with to give infinite variety to your wardrobe”.

With the coming of rationing in June 1941, women simply could not have new clothes as often as they used to so they had to learn new ways to make their wardrobe stretch. Not only did their allocated coupons prohibit it, convention and the increasing cost of clothing meant that women had to get inventive.

Having a selection of dresses and outfits that could serve any purpose, from day to evening wear was key, and the same with such things as coats which were expensive, used a lot of coupons and needed to last a long time.

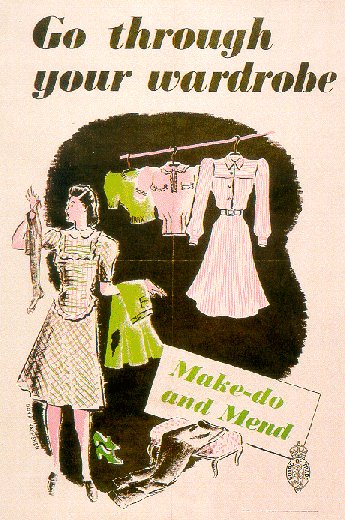

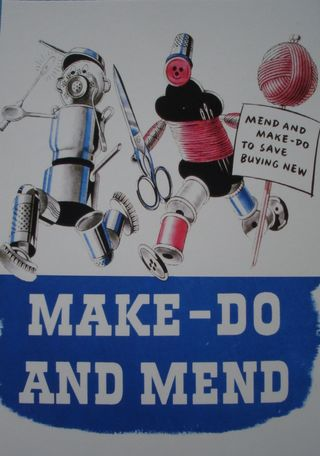

“Make do and mend” was the most important message for women regarding clothing. Under no circumstances would a woman go out looking tatty but she would have had clothes that had been carefully repaired a number of times. Just because there was a war on, this did not mean you could get away with holes in your clothes – they would have been mended.

Under rationing the conversion of men’s suits (as they didn’t need them while they were away at war) became common. “Your new suit from his old one” was a celebrated mantra.

Women’s magazines were full of suggestions: buy a frock in a light colour so it can later be dyed to give a fresh look to an old garment; make/buy/convert detachable collars for dresses to give a different look; rehash multiple old dresses into one or two good new ones were all widely accepted solutions.

Knitting became fashionable and particularly fair-isle because it allowed for the unravelling and re-use of wool from old knitted garments to save on coupons and cost.

Slacks became more popular as an acceptable form of dress for women because of the obvious practicalities when women had to go to work. But again, factions sprang up regarding their suitability. There was one side that thought they were better because of their practical uses and the saving of coupons on stockings. Then there were those that thought women were the wrong shape for trousers and that they were most unbecoming. However, as war progressed, they became more and more accepted.

Though clothes rationing was hard and times had changed, the English ‘stiff upper lip’ attitude prevailed and eventually women had to agree that every cloud has a silver lining:

“The average woman’s clothes may not be of as good material as they were in pre-war days and… her shoes and stockings are certainly very much inferior, but the total impression which she makes is neater, often smarter, usually altogether more chic. Forced to do without frills, she has learned something of the French woman’s appreciation of cut and line; limited by rationing to something less than half her pre-war purchases, she has learned that colour, to be used with effect, must also be used with discretion...” Civilian Supplies in Wartime Britain

There was then the question of ‘war workers’ garb. Those women who worked in factories needed clothing that was extremely practical and allowed them to work safely. Headscarves and turbans were commonly worn to protect stray hairs from catching in machinery. Snoods were also popular for this reason. Bib and brace overalls were considered as a great way to dress for factory work and were also very popular ‘on the land’. Short sleeves, apart from saving on fabric, were encouraged when working on or near machinery. Long sleeves were to be close fitting at the wrist or rolled above the elbows.

The pinafore was a common sight and almost accepted as a ‘uniform’ for housewives of all ages. They were often made from hubby’s unused shirts which could be converted by taking off the collar and neatening the neck, shortening the sleeves and making a waistband from the cut off part of the tail. “She wears it back to front because it then looks for all the world like a country smock!” Home Companion, July 1943. You could also get two house aprons from one old frock, according to Sew and Save, by discarding the sleeves, separating the back and front, making a few adjustments and turning the two halves into aprons with square bibs.

Accessories

Accessories were the key to success as rationing progressed. We all know that adding new accessories to an old outfit can completely change it and this was a lesson hard-learned during the war years.

Shoes became flatter during the war, with a maximum heel height of two inches imposed. Also, with the changing roles of women during the war years, heels became increasingly impractical. As the war progressed, materials for shoes were in short supply so shoes had to be looked after and even stockings had to be repaired if they got laddered, an idea that seems inconceivable to us today!

Hats were not rationed but became harder to get as the war went on, as well as being increasingly expensive. Many women got around this by knitting hats or berets for themselves and their families and the use of headscarves, snoods and turbans were a natty alternative to a hat in many cases.

Belts were popular as a way of freshening up the look of a much-worn dress. Narrow leather belts in bright colours, belts made of silk with embroidery as decoration and even crocheted belts were given by women’s magazines as a good way to accessorize.

Bags, as always, were an important part of a woman’s look. As the way people shopped in the 40’s was very different from today (it would almost be a daily thing, due to the lack of refrigerators in most homes) shopping bags were also an essential item of kit for a housewife. During rationing, many food/household items were hard to find so if you saw a queue, you would get in it as there was likely to be something good at the other end. Because of this, most women would carry around a shopping bag or basket at all times, just in case. It was not unusual also for people to always be carrying things they would need to occupy them in an air raid shelter (books, knitting, snacks etc) as you never knew when the siren would go off!

Clutch bags had been popular in the 30’s and early 40’s but as war progressed, bigger shoulder bags became the norm. And as leather became scarce, home-made bags were common and may be knitted or made from felt or string or scraps of fabric from other projects.

Jewellery was, as in any period of history, an important consideration in a woman’s outfit. Sweetheart brooches (or even rings, earrings and scarf pins) in the form of the regimental badge of a loved one were popular at the start of the war but the manufacture of them was stopped as war progressed. Most items of jewellery (apart from identification tags, cuff links and collar studs) were considered luxuries that the country could do without and so the manufacture of anything but the most utilitarian of articles was soon stopped. Second hand jewellery was allowed to be sold and was very popular. And of course, the well-off had their pre-war collections to fall back on. Other than that, it was back to make do and mend with many home-made items of jewellery springing up to cater for the lack of new items. Hand-made buttonholes made from felt or silk scarps were common as well as concoctions from old, broken pieces of jewellery re-used in new ways, adding bows and flowers here and there to create a new look. Wood, wire, wool, plastic and felt all became the raw materials for home-made jewellery as well as acorns, pinecones or rose-hips in some cases!

Civilian service badges were commonly worn by those ‘not on active service’ as were badges relating to certain ‘war-collection’ schemes in much the same way as we wear charity badges today, promoting and showing support to our chosen causes.

Watches were produced in a variety of shapes; round, square and hexagonal being the favourites. They were usually on leather straps, especially towards the end of the war as metals became scarce. Some watches had luminous dials, especially useful during the blackout.

Children

Hand-me downs were usual during the war years as families would try to help each other out during rationing. Children then, as now, got through clothes at an alarming rate!

Knitted clothing was common as, again, wool could be recycled and knitted garments are versatile for all weathers and occasions.

Babies’ clothing was very similar then to what we term as ‘traditional baby clothes’ today – the layette included gowns, vests, bibs, bonnets, matinee jackets and bootees much as it is today. Baby clothing was not introduced to rationing until 2 months after the start of the rationing scheme. Many babies would be wearing hand-made clothes because the coupon cost of materials was far less than that of ready-made garments.

Toddlers would be wearing bib and brace sets or dungarees and even knitted ‘jersey’ suits consisting of matching shirts and shorts. ‘Buster suits’ were very popular for this age group, consisting of a pair of shorts and a little shirt that would be buttoned together that the waist.

Boys would be wearing short trousers with long socks up until the age of twelve or thirteen, then long trousers. Often with a shirt and tank top and blazer or knitted jacket and maybe even a tie, their clothing (apart from the shorts) was very similar to that of a civilian man’s.

Short dresses were the thing for little girls, in cotton for daytime wear and velvet for best.

Most young children (both sexes) would be wearing sandals with ankle bars or t-bars. Sometimes boys might have lace-up shoes or boots and before the shortage of rubber became a problem, wellies or plimsolls would be a common sight.

Again, the wardrobe of the absent father might be raided for material for clothing – school shirts/blouses made from dad’s shirts, his flannel trousers being pressed into re-use as a new school dress. Children’s clothing was commonly made from old, worn-out adult clothes to save money and materials.

Very often, because of school regulations, school uniform had to double up as ‘best’ clothing because of the demands it placed upon the annual coupon allocation.

Dungarees were an acceptable form of clothing for a girl up until the age of eleven or twelve, especially with the renewed enthusiasm for this mode of dress with the ‘Dig for Victory’ campaign.

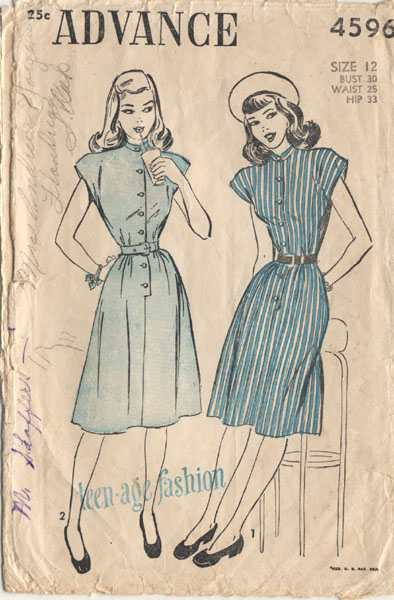

Older girls’ clothing (up until the age of around sixteen or seventeen) would be similar to that of their mothers but with a more youthful, simple cut.

Teenagers were just emerging as a separate fashion group and the advice for them was simple: wear “youthful, happy shades” such as hyacinth pink, primrose yellow, pale blue, teamed up with deeper shades such as the ubiquitous navy blue, bright moss green or nutty brown. Styles should be simple, never fussy, to bring out the freshness and natural beauty of the young. The teenager should look herself, and not attempt to dress like an older lady before her time.

Clothing ever-growing children was always going to be a problem during rationing and so the WVS was recruited in some areas to lead a ‘clothing exchange’ for children helping out mothers nationally. A “make do and mend” party would be attached to most of these exchanges to help renovate worn out clothing and make what people had to spare stretch a little further.

Hair

Women were under a lot of pressure to stay looking good despite all the hardships of daily life, such as digging for victory, make do and mending, cooking, cleaning and running for the air raid shelter and all this made hair styling a little bit of a chore.

It’s no wonder that shorter hair became more fashionable as war progressed but elaborate styles seem to have never lost their charm, even under all the dust and dirt they were faced with. Curls and quiffs, rolls and waves were inventively combined to produce and endless catalogue of hairstyles to suit faces of any shape or complexion!

Keeping hair clean was the first job, though it was usual to only wash hair once a week or even once a fortnight at that time. Shampoo was hard to get but there were alternatives such as soap flakes and even vinegar or lemon juice and castor oil.

As curls were so popular in the hair, setting was important. Most did this themselves, using curlers, rags or home setting lotions though some were able to afford to visit the salon and have a ‘permanent wave’ (perm). This had been popular for years before the war but as the country came under the shadow of austerity, many were criticised for having perms as it was seen as an unnecessary luxury (though this view was opposed by those that saw it as a woman’s duty to look good for morale, apparently the opinion that won the day!). The unreliable supply of electricity also posed a problem for salons, as did the summons to air raid shelters but the development of the non-electric perm helped in these cases.

Shorter hair was much easier for women to manage during these difficult times and many women in the armed services found that the ‘off the collar’ rule was far easier to follow if her hair was short.

Ribbons and flowers were a common sight in the hair of women who wanted to keep their look fresh and youthful, especially whilst hats were hard to come by. Those that simply did not have the time to keep their hair looking nice because of work or family commitments increasingly took to wearing headscarves, snoods and turbans. These kept their hair out of the way and covered up. To some, this look was also seen as patriotic – they were dressed for ‘doing their bit for the war effort’.

Make-up

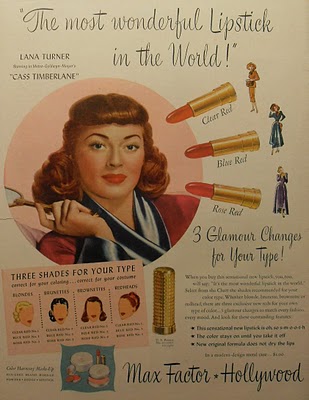

Make-up became scarce during the war. Indeed, its manufacture was banned for a short time though the outcry against this forced a small reappearance of a limited amount of products.

Make-up suffered the shortage of raw materials such as alcohol for making perfumes, nitro-cellulose for nail varnish and emollients (fat, oil and glycerine) to make products smooth and soft. Hence wartime quality was far inferior to what it had previously been, but women soldiered on with whatever they could get.

As you might imagine, many home-made solutions were being suggested by women’s magazines of the time, such as beetroot juice to stain the lips and boot polish as a mascara substitute. Scarcity of face powders forced a push towards encouraging women to keep a clear complexion in the absence of anything to cover it up. A healthy diet of fresh veg and plenty of water were suggested and advertisers latched on to this idea pressing home the message ‘inner cleanliness clears the skin’ (from an Andrews liver salts ad).

The face was treated much more roughly than we would find acceptable today and rubbing soap lather into the face with a soft nail brush and slapping the cheeks with a wet flannel to make the colour rise in them (for a ‘naturally rosy complexion’!) seemed to be good advice at the time.

To get the fashionable look, wartime women would have had sculpted brows, shaped with a pencil. They powdered their faces (if powder was available) and used rouge - either a cream rouge that went under the face powder or a powder rouge that went on top - teamed up with a matching lipstick. All advice was to never use a lipstick that did not match your rouge:

“If you’re absolutely stuck for matching rouge, why not use your lipstick? It’s not quite the same consistency as a cream rouge, but it does the job, and it looks better than going pale, or, much worse, using a clashing rouge…” Home Companion

However, all the attention seems to have been on the lips, creating a full, pouting lip line, emphasising the Cupid’s bow. Shades from pinky-red and cyclamen (an orangey pink) through bright scarlet red and into the soft brownish red tones seem to have been popular, depending on the complexion and season.

Eyes received the least attention with the merest dusting of shadow at most (usually none). Indeed, for ‘best’, women were advised to simply smear a little brilliantine or cold cream over the lids to make the eyes look larger. Mascara was applied to the top lashes only and was seen by some as “fast” so many women did not care for it at all.

Teenagers, then as now, were prone to experimentation with make-up, despite their parents’ protests. The advice to mother was to school their budding starlets in how to properly apply make-up, rather than forbidding it and forcing their girls to make a mess of putting it on. Here’s some advice from The Lady’s Companion on how wartime teenagers should look:

“Now if our young Miss Seventeen is to make the best of this joyous springtime of her life and looks, she must remain her pretty natural self. Not for her are rouges to dim the first roses… her bright young eyes must remain innocent of eye shadow and mascara yet. A pretty pastel lipstick, a little cream and powder – that is all she should allow herself. Her hair must be dressed simply but becomingly – brushed and brushed till it sheens and ripples like a field of corn a’blow.”

Nail varnish was popular in the early 1940’s though wartime constraints made it quite awful stuff and by 1943 it had all but disappeared. Long nails were considered a sign that one wasn’t working for the war effort, so short, well-manicured nails coated in pale shades were the thing whilst nail varnish was still available. By 1944 however, it was really not in use anymore.

During the course of the war years, the price of cosmetics went up by an average of 75%, making them unaffordable for many women. Black market items sprang up but often contained harmful substances having not been properly tested. So unless they were prepared to make their own, many women were forced, by the end of the war, to go without very much make-up at all.